Features

Do No Harm

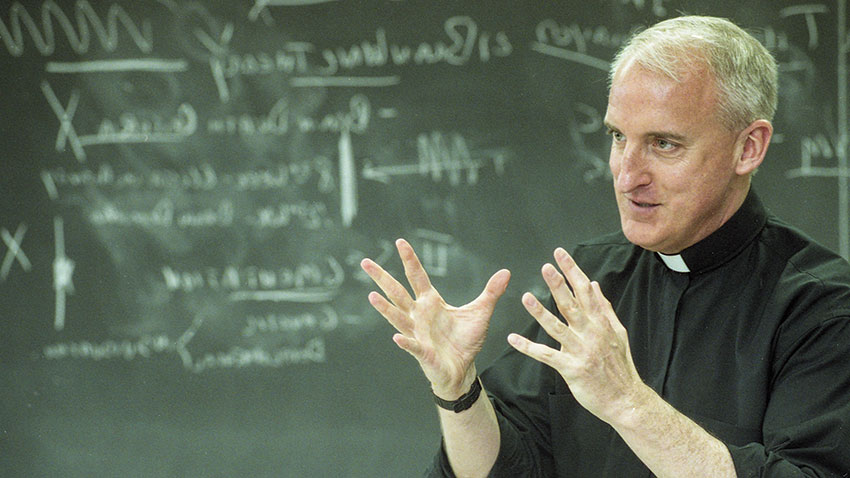

Peter Clark, S.J. '75 is an outspoken advocate of addressing the opioid crisis by creating safe injection sites in the city.

In October 2018, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney signed an executive order declaring the city’s opioid problem — which has sent neighborhoods around the area into atrophy — a “disaster.” “The crisis has created unacceptable conditions for Kensington and the surrounding neighborhood,” Kenney’s executive order states. “Nearly 150 people are camped on Frankford Avenue and Emerald Street, alone, with smaller encampments spread throughout the community. Drugs are bought, sold and injected openly … Streets, school yards and public parks are littered with trash, human waste and used syringes. Children and commuters dodge illegal activity on their way to school and work.”

The call to action, while monumental, was not surprising. More than 1,000 people died from opioid drug overdoses in Philadelphia in 2017. While 2018 numbers are not final, it’s estimated that another 1,000 deaths in the city will be opioid-addiction related. Nationwide, an estimated two million people struggle with opioid dependence; in 2016 and 2017, more than 130 people died from opioid-related drug overdoses every day in the U.S., according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

What is surprising, at least to some, is that a Jesuit priest — Peter Clark, S.J. ’75 — is an outspoken advocate of addressing the problem in a controversial way: by creating safe injection sites in the city.

In a study published in The Internet Journal of Public Health, the professor and his team of students and doctors supported the creation of Comprehensive User Engagement Sites (CUES) staffed by health care professionals who would supervise intravenous drug use and provide syringes, disposable cookers, matches, bottled water and tourniquets.

Clark’s work is driven by one of the Church’s most fundamental beliefs: All human life is sacred.

“We took a lot of pushback on [the safe injection sites]: ‘Why are you, as a Catholic ethicist, promoting giving clean needles to heroin addicts?’” Clark says. “But what we’re trying to do is based on the sanctity of life. Unless you’re ready for rehab, you’re not going to be successful. We’re trying to keep people alive until they’re ready to go into rehab. That’s our ultimate goal. I learned a long time ago that many people think ethics can be black and white. I think it’s gray in most places.”

As Clark has immersed himself in the issue, he’s spoken to countless people with a substance use disorder, the people who love them and the health care workers who struggle to keep them alive. Despite the fact that many who complete a substance use disorder treatment program or “rehab” go on to productive and satisfying lives in recovery, one person still struggling with the issue told Clark, “We are the disposable people.”

“That really hit home. They see themselves as people no one cares about. If they die, they die. That’s one less person to have to worry about,” Clark says. “That said a great deal to me: What kind of society are we if that’s what we really do think?”

I learned a long time ago that many people think ethics can be black and white. I think it's gray in most places."

'A Person of Conviction'

As a college professor, Clark teaches, counsels and mentors students. As founder and director of the University’s Institute of Clinical Bioethics (ICB), he works with doctors from around the world as they grapple with difficult ethical dilemmas and does weekly ethical teaching rounds at four local hospitals.

As a humanitarian, he uses both roles to help others. On a local level, Clark helms a project that serves the medical needs of tens of thousands of undocumented immigrants and is working with students to find ways to reduce childhood obesity and to explore the use of marijuana as a drug treatment option. Students working with Clark are also seeking improvements to health care overseas, looking to repurpose pacemakers and creating sustainable sanitary napkins.

“Like a lot of Jesuits I’ve met over the years, I wonder where he finds the time to do all of these things. He’s doing everything,” says Saint Joseph’s University President Mark C. Reed, Ed.D. “I’ve more or less told him that he has our support and we’ll stay out of his way. He’s earned that trust and credibility.”

Ann Marie Jursca Keffer, director of the University’s Faith-Justice Institute and an adjunct professor who has taught “Just Health Care in Developing Nations” with Clark for 20 years, agrees.

“He’s a person of conviction who’s driven by his moral compass and a faith that promotes social justice,” she says. “When he sees a need that he can intellectually and experientially solve, he gets to work.”

Joining the Jesuits

This is Clark’s third stint at Saint Joseph’s. His first was as a student. Growing up in Delaware County, Clark chose the University because it was the only local college that offered Latin American studies, and he was considering a future working with the U.S. State Department. He studied in Mexico City as an undergraduate, living with a local family. His experiences there are directly related to his current social justice work.

“I developed a real love for the Mexican people,” Clark says. “I also saw how the indigenous community wasn't treated well. You see their plight and you see Guatemalan and Hondurans coming through, desperate to make it to the United States. It was important to do something.”

John Rangel, chair of the Institute of Clinical Bioethics’ external advisory board, met Clark in Mexico. Even as a very young man, Clark was a leader, Rangel says. The two quickly became friends and remain close today.

“He’s true to himself and true to what he believes is the right way, and he’s happy to bring you along,” Rangel says. “He has a belief in the good in people and he has a way of bringing it out as well.”

Clark graduated from Saint Joseph’s with a bachelor’s in international relations and a minor in Latin American studies. He then went to work for AmeriCorps precursor VISTA, working with migrant farm workers in Texas. After completing a master’s in counseling psychology at Duquesne University in 1978, he returned to SJU as associate dean of students. One of his notable acts? Banning beer kegs from campus.

“I was not well-loved by the student body,” Clark remembers. “I was the disciplinarian.”

It was yet another case of Clark taking an unpopular or controversial position because it aligned with his beliefs. University supporter Brian Dooner ’83, an undergraduate at the time, met Clark during this era and saw he was more than a tough guy.

“If you got to know him, you saw he cared deeply about students,” Dooner says. “Peter inspires students … He had that effect on me.”

While overseeing student life on campus, Clark also got to know the Jesuit priests who lived and worked there. He decided to join the priesthood at age 30, much to his family’s surprise.

“They thought I was crazy. I was kind of a wild kid, not your typical holy roller,” Clark says. “I knew I wasn’t called to be a parish priest. I loved academia. I loved teaching. I wanted to teach at the university level and [the Jesuits] offered me that opportunity.”

He called his sister to tell her the news. She tested whether he was serious, reminding him of the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. When he affirmed his plans she gleefully claimed his car, stereo and TV.

Clark began studying at a Jesuit spirituality center in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, where, for two years, “You look at them, they look at you, and you learn to pray,” he says. His training included stints as a rookie police office, a prison psychologist and a live-in assistant to the disabled.

He and two other aspiring priests also set out on “Walking Pilgrimages,” traveling the 105 miles from Wernersville to Emmitsburg, Maryland on foot without money.

“You had to beg for food, water and lodging and you couldn’t tell anyone what you’re doing. It was a way of understanding what a mendicant order is: those religious orders that travel and live in poverty,” Clark says. “The reason I did it was to see if I could really put my trust in God. If I was going to do this Jesuit thing, I had to be able to 100 percent put my trust in God.”

One of the men broke his leg soon after his pilgrimage began and dropped out. The other persisted despite being attacked by a raccoon. And Clark? “I had a bed every night and food every day. I was never turned down once.”

We knew we needed to do something because we weren’t really helping these patients who are in need, who are the most vulnerable.”

Entering Academia

Clark got his first lesson in obedience when he told his Jesuit superiors that, of the three options available, he wanted to go to St. Louis to study for his master’s in philosophy. They assigned him to Fordham University instead.

His second lesson came not long after. With his philosophy degree in hand, Clark was ready to teach. He wanted to work in a high school. His provincial thought he should go to Loyola College in Baltimore to teach philosophy.

The provincial instructed Clark to pray for direction. “Whenever they give you that ‘pray about it’ stuff, you know you’re in trouble,” he jokes. But he did, and two weeks later, he told the provincial that Jesus had told him to go to one of the high schools.

“He said, ‘Well, Jesus told me you should go to Loyola College in Baltimore,’” Clark recalls.

Turns out that Jesus may have been speaking more clearly through the provincial: Clark ended up teaching medical ethics at Loyola, which kickstarted a lifelong career.

Clark was ordained in Baltimore in 1992 then went to Loyola University in Chicago to work towards a Ph.D. in Christian ethics with a specialization in biomedical ethics. That’s where he met Al Gustafson, who became a friend and, later, a member of the Institute of Clinical Bioethics’ external advisory board.

“From the beginning of the time that I knew him, Peter has always been interested in those who are vulnerable, those who are on the margins, those in need of justice,” Gustafson says. “He’s tireless in his devotion to those he cares about and that includes his family, his friends, his colleagues, the kids he mentors through the Institute. He has changed and shaped the lives of countless students through the time and attention he’s given them.”

Gustafson recalls a recent text that Clark had sent him to say he’d celebrated Mass that morning to mark the anniversary of the death of Gustafson’s son, Michael, who was 15 when he died from brain cancer in 2013.

“It was 3:30 in the morning, Philadelphia time, and he’d said Mass for our family. That, for me, is the perfect example of the man he is,” Gustafson says. “He’s constantly thinking of other people and their needs.”

Studying the Opioid Problem

After graduating with his Ph.D., Clark returned to Saint Joseph’s once more, this time to teach medical ethics. There were no ethics or bioethics programs at the time. He set out to change that.

“Medicine is becoming more complex. In the old days, medical ethics dealt with end of life issues: Can you turn the ventilator off? Can you remove the feeding tube? Now we’re morphing into things like genetics,” Clark says. “There are new issues coming up every day and somebody needs to send up the red flag to the idea that just because science says we can do something, we should. I’m not sure we should in every case.”

In his advisory work with the ICB, some of the ethical questions Clark receives from physicians relate to religion. Orthodox Jews draw a line between brain death and cardiac death. Orthodox Muslims aren’t to receive blood thinners made with pork products. Many Jehovah’s Witness followers decline blood transfusions. When a Buddhist dies, custom dictates that the deceased’s head is not moved for two hours for it is through there that the soul leaves the body.

“We had a resident who opened a window after a patient died. It was winter,” Clark recalls. “The nurse said, ‘What are you doing?’ but the mother said, ‘He’s allowing the soul to go to Heaven.’ The family was really impressed.”

It was during his regular hospital rounds at Darby’s Mercy Fitzgerald hospital that Clark noticed some of the young doctors were unhappy. They were frustrated by their dealings with patients suffering from substance use disorder, some of whom they saw repeatedly. One patient, hospitalized for an infection, overdosed in his hospital bed after he used his IV line to take heroin. Others were made so desperate by their struggles with substances that they would lie to doctors, saying they were in pain but allergic to non-opioid painkillers.

“We’d ask, ‘Did you offer them rehab?’ and they’d say, ‘Why would we do that? Last time, they signed out (against medical advice),’” Clark explains. “It was almost becoming a source of moral distress. We knew we needed to do something because we weren’t really helping these patients who are in need, who are the most vulnerable.”

Clark formed an opioid research team consisting of medical residents from Mercy, students from the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and SJU undergraduate research fellows. Their task: to study the opioid problem nationally and locally and to find creative ways to address it.

"They jumped into this project,” Clark says. He also warned Dr. Reed and leaders at Mercy that they could receive negative pushback. “They have backed us 100 percent,” Clark says. “That says a lot about them and about the institutions.”

By the Numbers: Opioids in Philadelphia

'An Intractable Social Problem'

About 30 years after they’d last parted, Clark and Dooner reconnected at an alumni event. It was like they’d seen each other just the day before.

“We picked up right where we left off,” Dooner says. “It’s remarkable how little we’d changed over the years.”

The pair reestablished a close relationship, and Dooner began to learn more about Clark’s work on and off campus.

“I appreciate the way that Jesuits bridge the worlds of scholarship and faith in action. Peter is a wonderful example of that,” Dooner says. “He has a big social footprint.”

Hearing of Clark’s recent work to address the opioid crisis, Dooner and his wife, University Board of Trustees member Marlene Sanchez Dooner ’83, decided to donate to Clark’s efforts, funding his safe injection sites research. Clark often says substance use disorder touches everyone without regard for race, income or education. The Dooners knew this, having lost a person very close to them to the disease.

“This is an intractable social problem and it’s all around us.” Dooner says. “It gets pretty dark out there for those who struggle with substances and their loved ones. I am certain that any SJU efforts that raise awareness of these issues among students and the University family can reduce harm and, in some cases, help save lives in our community.”

I knew I wasn’t called to be a parish priest. I loved academia. I loved teaching.”

Fighting the Opioid Epidemic

Part of the research team’s early work involved learning more about the patient population. It was eye-opening, says Mercy resident Sonul Gulati, who watched one of his first patients at the hospital, a 27-year-old woman, die not from a drug overdose but from an infection caused by reusing needles.

“This patient population is a lot different than we initially thought. A lot of these people come from very economically underprivileged backgrounds and often suffer from sexual trauma and physical abuse,” Gulati says. “We really should be bringing this patient population closer, not pushing them away.”

Mercy resident Rushabh Shah says he started thinking about his patients differently, approaching them with more understanding, after working on the opioid research project. The “care fatigue” lessened.

“Society has made us so guarded, and [the project has] forced us to look at this community in a certain way,” he says. “Being a part of this team has helped me view these people as people and not just ‘addicts.’ They’re just people dealing with something.”

The more controversial part of the research involved evaluating the establishment of safe injection sites or CUES. Clark and his research team looked at the success of a program in Vancouver, Canada, where people could have their drugs tested for potentially deadly Fentanyl contamination, get other health care services and, if desired, learn about rehab options.

“The administrators … stress that recovery can only be successful when the staff and users build trust with each other,” the team concluded in the report. “Thus, they make sure that the … staff is trained to create ‘respectful, tolerant relationships with individuals who are chronically marginalized and dehumanized’ so that staff can help users to move forward with their recovery by seeking detoxification.”

Since the safe injection sites were introduced in Vancouver in 2003, more than 3.6 million users have injected at the facilities. There have been almost 49,000 treatments for other medical conditions like wound care or pregnancy testing and 6,440 overdose interventions without a single death. The number of overdose deaths among residents living within 550 feet of the facilities has decreased by 35 percent; citywide, overdose deaths over the same period only decreased nine percent.

“Don’t get me wrong. I’m not an advocate of drugs. But I am an advocate of treating people with dignity and respect, and I think we have to do that where they’re at,” Clark says. “Nobody is immune from this. I think it’s our responsibility to do something, not only because we’re Catholics or Christians, but because we’re human beings.”

Olivia Nguyen ’19 says she initially hesitated when she was asked to join the opioid research team, believing safe injection sites weren’t a good idea. Then she did independent research and took to heart Clark’s words about caring for the whole person.

“Fr. Clark has helped make me the person I am today,” says Nguyen, who is thinking of taking a gap year before studying for a master’s in public health. “I’ve seen how much he cares about his students and working for the common good. I think he’s the reason I consider St. Joe’s home.”

The team’s report is now in the hands of Philadelphia Mayor Kenney, but the city has been slow to respond. Clark suspects it’s because the U.S. Department of Justice has said it will shut down such a site and charge those involved with a felony.

A nonprofit created with the intention of facilitating the creation of a safe injection site, Safehouse, counts among its advisors former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell and Sister Mary Scullion, R.S.M. ’76, also a member of Saint Joseph’s University Board of Trustees.

Clark, too, is trying to think creatively. During a meeting with the research undergraduates, he noted that the so-called federal “crack house statute” forbids distributing or possessing drugs in a particular structure.

“Maybe we could propose a mobile unit. A van, not a house. We could do what we want to do in a mobile unit,” he mused. “Or we could put up a tent in a parking lot, something that’s not permanent but portable.”

It seemed incongruous: A priest — an ethics professor at that — talking about ways to sidestep federal law. But it made sense to Clark. He still remembers being on a hospital consult a few years ago and being asked to counsel the mother of a patient who had overdosed on opioids and was brain dead. She wanted to speak to a priest before she made a decision regarding organ donation.

Clark listened as the young mother talked about how hard she’d worked to help her son, a bright, talented athlete, break the hold substances had on him.

“She had prayed and prayed and yet look what happened,” he says. “I don’t think I was ever moved by an experience in the hospital the way I was that afternoon. Even after his death, his mom was still struggling with his addiction. You could feel the love she had for him, but also the frustration and even anger that his beautiful life was now gone.”

The woman decided to allow her son’s organs to be donated to other patients, telling Clark, “Maybe this is his greatest gift of all, the gift of life for others.” Those words have stayed with him.

“The young man in my story did give the gift of life for others that day,” Clark says. “But in many ways, he also inspired me and our team to save as many lives as we can today.”

Natalie Pompilio is a Philadelphia-based writer who contributes to The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Washington Post, The Star-Ledger (Newark) and the Associated Press. She is the author of "Walking Philadelphia: 30 Tours Exploring Art, Architecture, History and Little-Known Gems" (Wilderness Press, 2017) and co-author of "More Philadelphia Murals and the Stories They Tell" (Temple U. Press, 2006).