Lessons from 1940s Shanghai: 5 Questions with James Carter, Ph.D.

James Carter, Ph.D., discusses his latest book, Champions Day, and what he hopes Shanghai’s history can teach our current world.

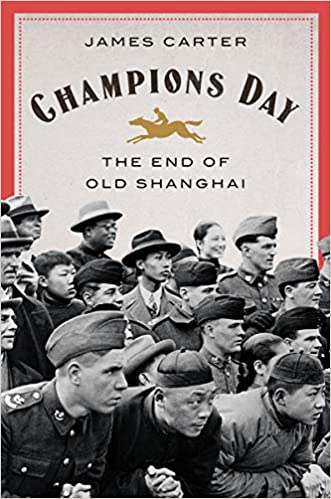

Shanghai, China in the early 1940s was one of the most important ports in Asia and a uniquely international city as a result of the Americans, British, French and Japanese establishing territories there in the 19th century. In a new book, James Carter, Ph.D., professor and chair of the history department at Saint Joseph’s University, delves into the complex history of Shanghai through the lens of a single day: November 12, 1941, weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai is named after one of the events of that day, when Chinese and Westerners alike gathered at the Shanghai Race Club to bet on horse racing.

Shanghai, China in the early 1940s was one of the most important ports in Asia and a uniquely international city as a result of the Americans, British, French and Japanese establishing territories there in the 19th century. In a new book, James Carter, Ph.D., professor and chair of the history department at Saint Joseph’s University, delves into the complex history of Shanghai through the lens of a single day: November 12, 1941, weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai is named after one of the events of that day, when Chinese and Westerners alike gathered at the Shanghai Race Club to bet on horse racing.

Carter recently sat down to discuss how the book came to be and the lessons he hopes Shanghai’s history can teach our current world. An edited transcript of the conversation appears below.

How did you choose this topic?

James Carter: My research writing has focused on modern Chinese history, and especially on the interactions between China and the West. I have been especially interested in how that interaction played out on an individual level — not how nations interacted, but how individuals did. I’ve also been interested in sportswriting, and worked as a sports editor and writer in college, so the fact that the Shanghai Race Club was a place where Chinese and Westerners interacted was a perfect way to explore my interests and uncover the ways that Shanghai developed into a unique Chinese-Western place.

What are some of the more interesting stories from Shanghai’s history that you came across when writing this book?

James Carter: I think the whole story is fascinating. The characters are each more interesting than the next. Liza Hardoon, a French-Chinese woman, was the wealthiest woman in Asia when she died, and her funeral, which was held on Champions Day, 1941, consisted of a mixture of Buddhist and Jewish elements.

There was also Cornell Franklin, an American judge from Mississippi who was the unofficial head of the American community in Shanghai. Besides his time in Shanghai and serving as a judge in Hawaii, his first wife left him for [author] William Faulkner, which was not something I expected to find.

Overall, it’s just the unlikely setting of a racetrack holding races while World War II closed in around them. The International Settlement of Shanghai was neutral from 1937 to 1941 while the rest of China was at war. The spectacle of people watching horse races in the midst of the 20th century’s greatest catastrophe was surreal.

We should look to our past for models of what is possible, but also be reminded that we must not take anything for granted. Everything in this world is fragile."

James Carter, Ph.D.

Professor of HistoryWhat was your research process for Champions Day?

Carter: I worked a lot with newspapers from that time period, mainly in English and Chinese. I did a lot of my work at the Xujiahui Library in Shanghai which, interestingly, is an old Jesuit library. The compound was left to the Jesuits by an early convert to Catholicism, and the Jesuit order built an orphanage, church, and library there — all still standing, right near a subway station in Shanghai. It houses a huge collection of newspapers and books from the era I was researching.

[Saint Joseph’s] Nealis Program in Asian Studies was invaluable in helping me acquire digital databases that I have used for the book. Many of these (including The North China Daily News and The North China Herald) are sources I have used not only for my own research, but also with students. Not many students are able to use Chinese-language primary sources, but these are in English and are really useful for History seminars. I was also able to use sources in New York, Washington, D.C., London, and Hong Kong.

What do you hope people will learn from your book?

Carter: I hope they will get a glimpse into a unique time and place. Shanghai was a racist and colonial city in the 1930s and 1940s, but it was also a cosmopolitan and outward looking one. It was always strongest and most successful when it was open to the world. I hope that we can find ways to counter the tendency in the world today to turn inwards by seeing that we are stronger when the world comes together, but also that it can only last if we work against forces like racism and segregation.

Do you see any lessons for us today from what happened in Shanghai in the 1940s?

Carter: The people in Shanghai, 1941, took many things for granted. A few years before, theirs had been one of the world’s most prosperous cities. It all came crashing down [during the war]. We should look to our past for models of what is possible, but also be reminded that we must not take anything for granted. Everything in this world is fragile.